Hearts of Men: How Three Women Wielded Power in Medieval England

See also, three lesser-known historical badasses

Welcome to my new segment called History Bytes! In this newsletter, I’ll share mini essays or lists about different historical topics, usually centered on my particular favorites: ancient history, English history, the Renaissance, the Black Death, American gold rushes, and medieval/early modern European history. These will differ from the biweekly issues where I combine a brief history of a topic or event with related books and historical objects or places.

This inaugural segment focuses on three women from medieval England who wielded power in their own right. It’s important to keep in mind that in the Middle Ages, women in positions of power often inherited their titles or derived their positions from their fathers or husbands. Despite this, these women influenced important events or the times in which they lived on their own merits and deserve recognition.

Who are these incredible women? In this article, you’ll learn about:

In March 2021, the Getty Museum asked followers on Facebook and Instagram to submit some of their questions about women’s lives in the Middle Ages, and curators answered their questions. It’s a nice high-level overview that serves as a good grounding point for the rest of this article!

The Role of Women in the Medieval Period

Much has been written about women’s roles in the Middle Ages from a wide variety of perspectives. It’s not my intent to reinvent the wheel, but understanding how women operated within their spheres highlight the extent to which the women listed below exerted their power and influence despite political and societal constraints.

Generally speaking, medieval society considered women inferior to men due to their alleged physical and emotional weaknesses, sexual organs and proclivities, and humors.1 The rise of Christianity propagated and cemented the women’s inferiority complex crusade through the teachings of St. Paul and Augustine of Hippo among others.2

As such, priests and other clergy and laymen preached the subordination of women to their husbands, and, by large, to any male guardian in their lives. Their primary purpose lay in the marriage market, useful for sealing alliances, staving off military conflicts, and bringing forth heirs.

As Jennifer Ward comments, “All these ideas [scientific, medical, religious, etc.], taken together, imply considerable ambiguity and ambivalence of attitudes towards women,” leading to a “lack of individual identity.”3 And yet, the situation was a lot more complex.

The church saw husband and wife as complementing each other and stressed a relationship of love and mutual counselling. From at least the twelfth century, the church saw marriage as based on the consent of both parties to the union. It set its face against divorce, and aimed at preventing the husband from simply abandoning his wife. The evidence from the twelfth century onwards shows women being treated as people in their own right, although they had to accept a subordinate role.4

Again, in a general sense, medieval women typically only wielded power and influence in two ways: as a widow and in religious communities. Laws allowed widows to retain one-third of their deceased husband’s properties - even if she remarried - and she could conduct business transactions in her own name among other things. Women in religious communities avoided marriage, devoted themselves to charity and prayer, and often were educated and assumed power and status in their own right.

On the whole, women in western European medieval history occupied a multifaceted but subordinate role to men. The ladies listed below, however, offer us some insights into how some women exercised agency and independence in their lives.

Eadgifu of Kent

In Anglo-Saxon England, rarely were women recorded exercising power in their own right. One minor exception to this was Eadgifu of Kent (c. 903 - in/after 966 CE). Eadgifu was born to Sigehelm, the Ealdorman of Kent, who was killed at the Battle of the Holme, an incredibly important battle in Anglo-Saxon history.

Around 919, the lady married, as his third wife, Edward the Elder, the son of King Alfred the Great. They had three children: a daughter Eadburh, and two sons, Edmund and Eadred. Edward died in 924, leaving his wife a widow around the age of 25. Her whereabouts during the reign of Edward’s son Æthelstan remain obscured, but the queen rose to prominence during the reign of her sons. Edmund reigned from 939 to 946, and Eadred ruled from 946 to 955.

Sources documenting the movements of Anglo-Saxon women, even royals and noblewomen, remain sparse. What we do know about how they showed their influence typically comes from charters, chroniclers, and religious documents.

In Eadgifu’s case, she appeared on witness lists for royal decrees right after her sons, before others of importance such as prominent noblemen and clergy.5 She also advised the appointments of important clergyman, endowed religious institutions, and greatly assisted in the expansion of monasticism in the tenth century.

Margaret of Hereford

Margaret of Hereford (c. 1122/1123 - 1197) came from an Anglo-Norman family. Sometime before 1139, Margaret married Humphrey de Bohun, later steward under King Henry I. Sometime before 1139, Margaret married Humphrey de Bohun, later steward under King Henry I.

Margaret inherited titles and responsibilities following the deaths of her father and five brothers. This included the lordship of Herefordshire and the office of Constable of England. As lady, Margaret was the benefactress for many religious institutions, assisted Angevin kings, and confirmed land grants for her tenants.

She remained the lady of Herefordshire and exercised power until her death. The role of Constable eventually passed to her descendants.

Nicola de la Haye

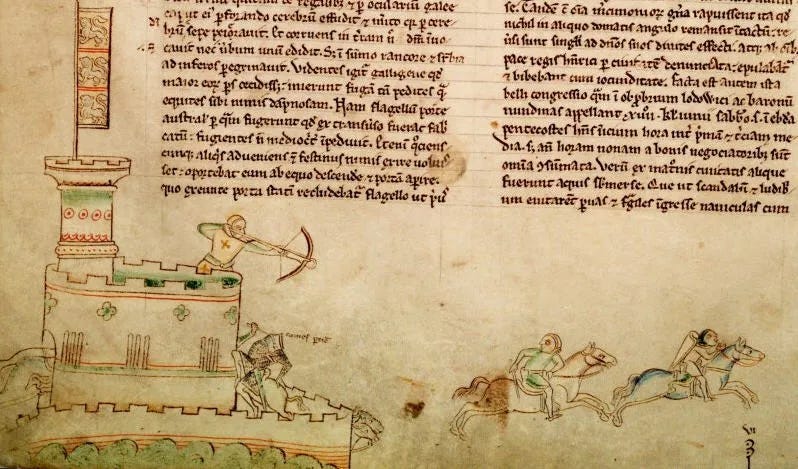

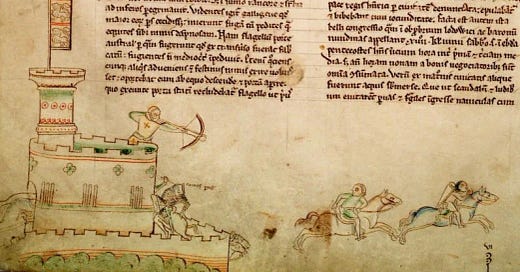

In the Middle Ages, castles served as fortresses of protection for and dominance over an area. Effective running of castles happened under castellans, or castle governors. Most castellans were men, but Nicola de la Haye (c. 1150 - c. 1230) just happened to be a woman.

The daughter of Robert de la Haye and Matilda Vernon, de la Haye descended from a prominent Lincolnshire family. After her father’s death in 1169, Nicola inherited position of castellan of Lincoln Castle and sheriff of Lincolnshire, a post exercised by her husbands - William de Erneis and Gerard de Camville - jure uxoris.

The Battle of Lincoln during the First Barons’ War tested Nicola’s ability as castellan. The First Barons’ War was a conflict between King John of England and his rebel barons who invited a French prince to invade England and topple John’s rule. John had reaffirmed Nicola in both of her posts, and she held Lincoln Castle loyally whilst under siege. By May 1217, royal forces reinforced Lincoln’s garrison and defeated the rebel soldiers once and for all. Nicola’s brave actions helped save England from a foreign invader.

Sources & Further Reading

Bavel, T.J. van. “Augustine’s View on Women.” Augustiniana 39, no. 1/2 (1989): 5–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44992476.

Hanley, Catherine. 1217. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2024.

Hart, Cyril. “Two Queens of England.” Ampleforth Journal 82, no. 2 (1977): 10-15.

Rivers, Theodore John. “Widows’ Rights in Anglo-Saxon Law.” The American Journal of Legal History 19, no. 3 (July 1975): 208-215.

Ward, Jennifer. Women in England in the Middle Ages. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006.

The concept of humors dates back to the Ancient Greeks, primarily Hippocrates and Galen. It was thought that humans were made up of four humors - black bile (melancholy), yellow or red bile, blood, and phlegm - and contributed to four psychological temperaments: melancholic, sanguine, choleric, and phlegmatic. The humors also correlated to the four elements: water, fire, earth, and air. Jennifer Ward writes in Women in England During the Middle Ages that “Usually one or two qualities were dominant, but whereas men were considered choleric and sanguine, deriving their heat from fire and air, women, it was thought, tended to be cold and moist (as derived from the elements of water and earth) and to be phlegmatic and melancholic” (p. 2).

See T.J. van Bavel, “Augustine’s View on Women” for an exploration on the varying facets of Augustine’s viewpoints on the fairer sex.

Jennifer Ward, Women in England in the Middle Ages (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006), 4.

Ibid., 4.

Cyril Hart, “Two Queens of England,” Ampleforth Journal 82, no. 2 (1977), 10.

Fascinating! Each one would make an awesome heroine in a historical fiction novel :)

So interesting! I enjoyed it so much I had to do a bit of digging on my own- my favorite thing ☺️

I cannot believe a woman held the position of constable ! Super cool!