Issue No. 31: Of Ancient Pharoi & Anglo-Norman Parapets, Part Two

Operation Dynamo, underground tunnels, and Churchillian oration.

“In the midst of our defeat glory came to the island people, united and unconquerable; and the tale of the Dunkirk beaches will shine in whatever records are preserved of our affairs.” ~ Winston Churchill

In the last issue of Musings, I wrote about Dover Castle and its role during the First Barons’ War (1215-1217), a conflict in which rebel magnates - unhappy with the rule of King John - invited the French prince Louis to invade the country and usurp John's throne. In part two of my Dover Castle series, I write on Operation Dynamo - a covert World War II operation that oversaw the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied troops from the shores of Dunkirk, France between May 26 and June 4, 1940.

As mentioned in Part One, Dover Castle’s strategic position at the English Channel's narrowest point between England and France has historically made it a key defensive location. During World War II, however, Dover’s proximity to Nazi-occupied France possessed both benefits and consequences. The distance made the city vulnerable to cross-channel shelling and other such offences, but on the other hand, it aided in the devisement of such a scheme that it inspired a Christopher Nolan movie. Over eight hundred years later, Dover Castle yet again played a key part in England’s defense.

As a disclaimer, please note I am not an expert in military history, and World War II history is complex and dense. Therefore, I aim to be as succinct and clear on such topics as I can for similar readers, but I’ll provide some additional resources for those who desire a deeper dive into this topic. Additionally, if you notice any errors, comment below, but please be kind.

Dover Castle & Operation Dynamo

Prelude: The German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

Beginning on May 10, 1940, the German military pressed against the country’s border with France and launched offensive maneuvers against many nations on the Western Front - a term encompassing western European countries including Denmark, Norway, France, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. German land and air forces advanced quickly through Holland and Belgium, overwhelming any Allied resistance - though Norman Franks notes that the German attack was not unexpected.1 Germany’s rapid advance pushed Allied forces, including the Britain Expeditionary Force, to retreat towards the Channel coast.

To avoid further bloodshed and casualties, British officials at home - specifically Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command - deemed it necessary to halt the sending of more troops in an effort to maintain a minimum needed to protect Great Britain.

Sir Dowding wrote to the Under Secretary of State at the Air Ministry on May 16, 1940, about the situation:

Sir,

I have the honor to refer to the very serious calls which have recently been made upon the Home Defence Fighter Units in an attempt to stem the German invasion on the Continent.

I hope and believe that our Armies may yet be victorious in France and Belgium, but we have to face the possibility that they may be defeated.

In this case, I presume that there is no-one who will deny that England should fight on, even though the remainder of the Continent of Europe is dominated by the Germans.

For this purpose it is necessary to retain some minimum fighter strength in this country and I must request that the Air Council will inform me what they consider this minimum strength to be, in order that I may make my dispositions accordingly…

Once a decision has been reached…it should be made clear to the Allied Commanders on the Continent that not a single aeroplane from Fighter Command beyond the limit will be sent across the Channel, no matter how desperate the situation may become…

I must therefore request that as a matter of paramount urgency the Air Ministry will consider and decide what level of strength if to be left to the Fighter Command for the defence of this country, and will assure me that when this level has been reached, not one fighter will be sent across the Channel however urgent and insistent the appeals for help may be…

…[I]f the Home Defence Force is drained away in desperate attempts to remedy the situation in France, defeat in France will involve the final, complete and irremediable defeat of this country.2

If the British military no longer sent forces to reinforce their troops on the Continent, then what would be the plan moving forward? The answer? A mass evacuation of Allied forces.

The Evacuation

By May 19, 1940, General Viscount John Gort, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, was considering an evacuation of troops from a number of French ports, namely Calais, Boulogne, and Dunkirk.3 The following day, the British War Cabinet began planning the operation in earnest. Winston Churchill - the newly-minted Prime Minister, having started his tenure on May 10th - later recalled:

At the morning War Cabinet on May the 20, we again discussed the situation of our Army. Even on the assumption of a successful fighting retreat to the Somme [a river in northern France], I thought it likely that considerable numbers might be cut off or driven back to the sea. It is recorded in the minutes of the meeting: “The Prime Minister thought that as a precautionary measure the Admiralty should assemble a large number of small vessels in readiness to proceed to ports and inlets on the French coast.”4

Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay was tapped to implement the evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo. The operation’s headquarters lay deep beneath Dover Castle in chalk-hewn tunnels originally designed as barracks for soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars. Some say the code name came from a dynamo - an electricity-generating machine - housed in the operations room, but English Heritage refutes this, saying it was simply a code word.5 In any case, the Admiralty requested a survey of ships and vessels suitable for an evacuation, the order for which came on May 26th. Churchill reported, prior to the requisition of Dutch vessels, the available boats consisted of “thirty craft of passenger-ferry type, twelve naval drifters, and six small coasters”.6

The evacuation began on May 26, 1940, when the War Office sent a telegram to Lord Gort, authorizing him to “operate towards the [Channel] coast forthwith in conjunction with the French and Belgian armies.”7 The Allied retreat was not easy as they occupied a rapidly-compressing segment of land from Lille to the south, Gravelines to the west, and Nieuport to the east.8 As shown in the map below, German attacks battered the beleaguered British, French, and Belgian troops.

The evacuation started slowly. Without the benefit of cover, the Allied forces were vulnerable to both land and air attacks. Furthermore, the Germans destroyed the main jetties at Dunkirk so larger ships such as destroyers could not dock. Instead, troops had to board smaller boats, which in turn ferried them to the larger ones out at sea. The first day saw the rescue of only 8000 soldiers. Unfavorable conditions and German attacks, however, failed to deter the brave and resilient rescuers and troops. Over the next nine days, around one thousand naval and civilian vessels rescued 338,226 troops.

The Aftermath

Despite the astonishing success of Operation Dynamo, the Allies still suffered heavy losses. On a human scale, the BEF suffered approximately 68,000 casualties, including 3500 killed and 13,053 wounded. Still others became prisoners of war. The army also abandoned most of their heavy artillery, vehicles, tanks, ammunitions, supplies, and fuel in the retreat to Dunkirk. Furthermore, the Royal and French navies lost a sum total of nine destroyers with some nineteen damaged as well as additional damaged and sunken smaller vessels. The Royal Air Force lost 145 aircraft while the German Luftwaffe lost 156 aircraft throughout the nine-day duration of Operation Dynamo.

Despite these losses, the evacuation boosted British morale and sealed itself in British memory, especially after the war. The BEF and other forces would live to fight another day, and this had implications for the remainder of World War II. Had the evacuation not occurred, it’s quite possible that the Allied tides of war would have drastically changed, and not for the better.

Churchill cautioned that, “We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.”9 But, he also celebrated the victory: “In the midst of our defeat glory came to the island people, united and unconquerable; and the tale of the Dunkirk beaches will shine in whatever records are preserved of our affairs.”10

It’s important to note, however, as Penny Summerfield argues, that the legend and legacy of Dunkirk is not concrete. Rather, depictions and perspectives shifted during both during and shortly after the war:

[T] popular memory of Dunkirk was nourished by competing accounts and animated from multiple angles of vision from 1940-1958. Dunkirk was constructed in wartime as an iconic national event to which the sea was central, yet there were at least two versions. In one ‘the nation’ was elided with the armed forces, specifically the Navy; others, particularly those emanating from America, prioritized the civilians of the small boats [volunteers who assisted with transporting soldiers from Dunkirk’s beaches and harbor during the evacuation] and, by implication, claimed the second world war for ‘the people’.11

As with many aspects of World War II, the evacuation of Dunkirk is subject to a variety of interpretations, perspectives, and historical discussions. Still, the images of soldiers wading through the sea towards waiting boats and Churchill’s powerful words present an evocative testament about a harrowing moment in military history.

Suggested Reading: Their Finest Hour by Winston Churchill

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill needs no introduction. He served during World War II and was known as a powerful orator. In doing research for this post, I relied heavily on his recounting of events from May to December 1940, collected in Their Finest Hour (The Second World War). It’s important to read this with a critical lens, especially given the time in which Churchill wrote and his subject matter. It is, however, a useful primary source for anyone interested in Operation Dynamo and the military and political aspects surrounding it.

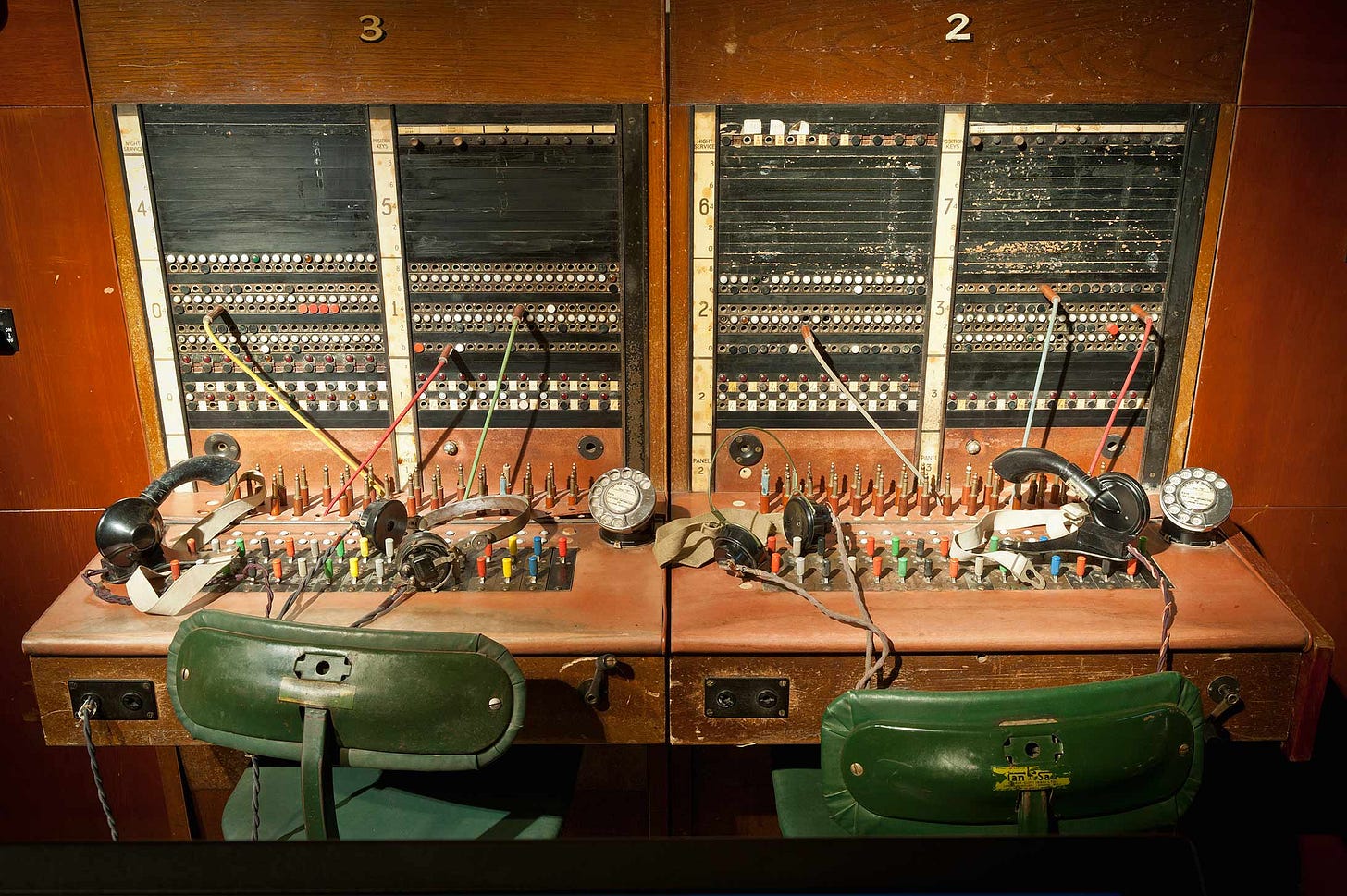

Related Artifact: Telephone Exchange, 1939-1945

This telephone exchange dates from the Second World War and was used to help facilitate communications. I’m uncertain if this particular one was used in Operation Dynamo, but given that it dates from 1939, it’s very likely. This exchange is located in Dover Castle’s wartime tunnels (also known as casements), which served as both the headquarters for the Dunkirk evacuation as well as a hospital.

From English Heritage:

“These Private Manual Branch Exchanges (PMBXs) are of the type known to have been at Dover in the 1940s. They were called ‘manual’ because they required the caller to dial through to the exchange rather than the connection being ‘automatic’. The exchange operator would then ring the outside line, wait for the receiver to pick up, and then join the caller’s line through to its destination by physically plugging the relevant wire into place.

Although exchanges were sometimes used by men, the operators were typically members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service and Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branches of the Navy and Army respectively.”12

Artifact Description

Title: Telephone Exchange

Date: 1939-1945

Material: Wood

Location: Dover wartime tunnels, Dover Castle, Dover, Kent, Great Britain

Sources & Further Reading

Atkin, Ronald. Pillar of Fire: Dunkirk 1940. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1990.

Churchill, Winston. Their Finest Hour. Boston; Toronto: Houghton Mifflin, 1949.

English Heritage. “Operation Dynamo: Things You Need to Know About the Dunkirk Evacuation.” https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/operation-dynamo-things-you-need-to-know/ (accessed January 27, 2025).

Franks, Norman. Air Battle for Dunkirk. London: Grub Street Publishing, 2006.

Hendley, Darren. “The letter that changed the course of history.” Aviation Classics. February 6, 2018. https://www.aviationclassics.co.uk/the-letter-that-changed-the-course-of-history/ (accessed January 21, 2025).

Summerfield, Penny. “Dunkirk and the Popular Memory of Britain at War, 1940–58.” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 4 (2010): 788–811. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25764582.

Featured image: Troops on the beach at Dunkirk awaiting evacuation (© Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Norman Franks, Air Battle for Dunkirk (London: Grub Street Publishing, 2006).

Darren Hendley, “The letter that changed the course of history,” Aviation Classics, February 6, 2018, https://www.aviationclassics.co.uk/the-letter-that-changed-the-course-of-history/ (accessed January 21, 2025).

Winston Churchill, Their Finest Hour (Boston; Toronto: Houghton Mifflin, 1949), 59.

Ibid., 58.

Ronald Atkin, Pillar of Fire: Dunkirk 1940 (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1990), 126; English Heritage, “Operation Dynamo: Things You Need to Know About the Dunkirk Evacuation,” https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/operation-dynamo-things-you-need-to-know/ (accessed January 27, 2025).

Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 59.

Ibid., 84.

Atkin, Pillar of Fire, 128.

Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 115.

Ibid., 124.

Penny Summerfield, “Dunkirk and the Popular Memory of Britain at War, 1940–58,” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 4 (October 2010): 809.

English Heritage, “Dover Secret Wartime Tunnels Collection Highlights,” https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/collection/, accessed January 28, 2025.