Issue No. 32: Of Merrie Gents & Miss Gwyn

Nell Gwyn, her relationship with Charles II, and her contrast with one named Squintabella.

“The English people have always entertained a peculiar liking for Nell Gwyn. There is a sort of indulgence towards her not generally conceded to any other woman of her class. Thousands are attracted by her name, they know not why, and do not stay to inquire.” ~ Peter Cunningham

King Charles II (r. 1660 - 1685) was one of those “larger than life” monarchs whose sordid life makes for fascinating exploration. He loved women, and they loved him back. Though he and his interminably patient queen Catherine of Braganza did not have any surviving children, this “Merrie Monarch” left behind a string of children that would have formed their own American football team. The story of Charles and his mistresses is often (quite literally) titillating but also reflects on the ever-present inequal power balance between men and woman in Restoration England and how some women achieved their own ambitions through their association with royalty or nobility.

Nell Gwyn takes center stage for this issue. She’s unique among the more prominent of Charles’ mistresses in that she hailed from ye olde commonfolk. Her plebeian upbringing endeared her to many and contrasted her against Charles’ more patrician ones such as Barbara Palmer; Duchess of Cleveland; Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth; and Lucy Walter.

The Life & Times of One Nell Gwyn

Common Beginnings

Nell Gwyn’s early life remains obscured, including her parentage, her birthdate, and her birthplace. She came from humble origins, the daughter of an Ellen (occasionally called Eleanor or Helena, depending on the source) Gwyn and an undetermined father. Her father’s story is murky. “Her father, it is said, was Captain Thomas Gwyn, of an ancient family in Wales,” writes Peter Cunningham in his 1851 biography of Nell. “The name certainly is of Welch extraction, and the descent may be admitted without adopting the captaincy; for by other hitherto received accounts her father was a fruiterer in Covent Garden.”1 Her descendant Charles Beauclerk also strongly supports the connection to Wales.2

The exact circumstances of Nell’s birth also remain a mystery. Cunningham and Beauclerk posit a birthdate of February 2, 1650, as determined by the 17th-century antiquarian and astrologer Elias Ashmole. Other sources and historians consider 1642 the likely year instead. Additionally, three different locations claim status as her birthplace: London, Oxford, and Hereford, with Beauclerk favoring Oxford as the most likely candidate.3 Though her birthplace and birthdate can help us interpret her story in different ways, Nell’s common upbringing played a key role not only in her relations with King Charles but also the general London populace.

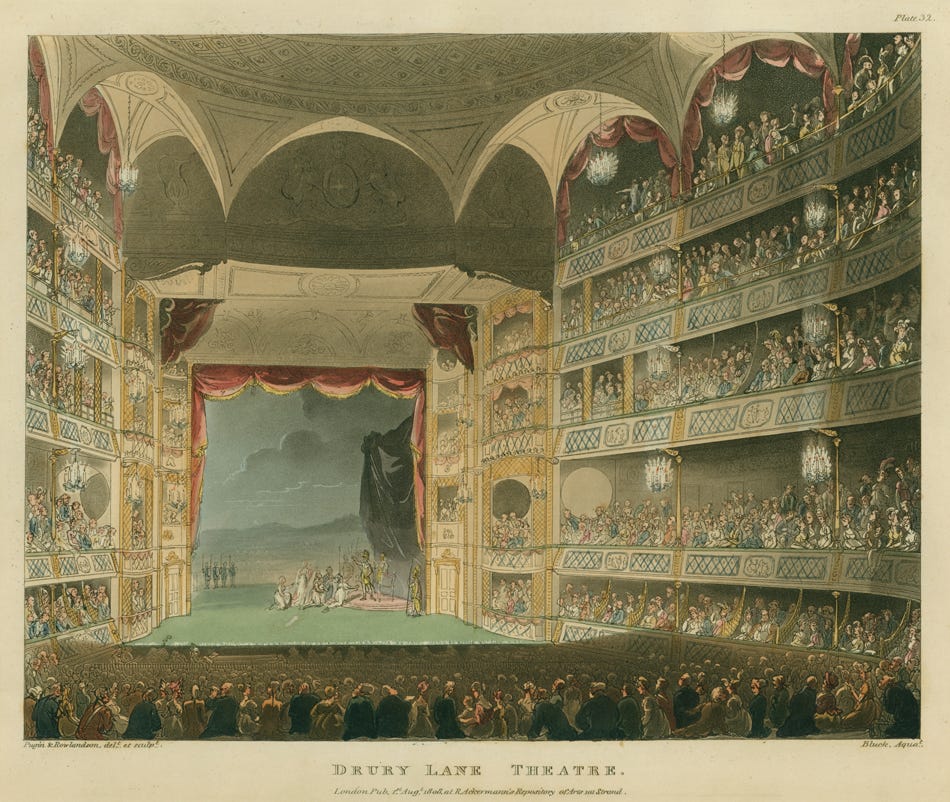

As a young girl, Nell worked as an orange seller, hawking her wares outside the King’s Theatre on London’s Drury Lane. During the Interregnum - the period between 1649 and 1660 when England fell under the rule of Oliver Cromwell and the Parliamentarians - theatre had been outlawed as a frivolity unsuitable for a civilized society. When King Charles II returned in May 1660 from exile in western Europe, ushering in the Restoration, theatre, and other forms of culture and entertainment returned with aplomb.

Restoration London was an exciting place to be…The King was a man who took an interest in human endeavour of every kind. Under his benign - some would say casual - rule, culture flourished: the theatres reopened, the arts and sciences burgeoned, trade boomed, investment soared and the people resumed their pastimes.4

Charles and his followers also brought Continental flair to England in the form of “music, paintings, fashion, furniture, food, gardens, architecture, the modern stage, court etiquette, gambling (of which Charles disapproved), pornography, champagne and a certain Gallic urbanity that was roundly resented by the bulk of Englishmen.”5

Women taking the stage formed a key difference in pre-Restoration and Restoration theatre. At the behest of manager Thomas Killigrew, Nell joined the King’s Company in 1664, one of two enterprises officially licensed to operate in London.6 The young girl trained under two prominent actors: John Lacy and Charles Hart.

Although the title and date of her theatrical debut is unknown, Nell’s first recorded appearance occurred in March 1665 when she played Cydaria, the daughter of the Emperor Montezuma, in John Dryden’s The Indian Emperor opposite Hart. The actor played her love interest Hernán Cortés. Nell’s looks, her wit, and her reputation as an actress endeared her to many, including those among the nobility. She maintained an affair with Charles Hart until about 1667 and then moved on to Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst, later 6th Earl of Dorset. But it would not be long until Nell Gwyn attracted the attention of an even more powerful figure: the king.

The King, Pretty, Witty Nell, & Squintabella

Becoming the King’s Mistress

Later in 1667, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, desired to exploit a quarrel between Charles II and the king’s principal mistress, George’s cousin Barbara Palmer, Lady Castlemaine, a lovely and vibrant noblewoman with brunette hair and violet eyes. The king had kept her since 1660, and they had borne several children together. In an effort to supplant this most powerful mistress, Buckingham devised a plan involving Nell and her fellow actress Moll Davis whereby either woman would replace Lady Castlemaine.

Initially, however, Buckingham’s plan partially failed as Nell requested the goodly sum of £500 per annum for her upkeep. Moll became Charles’ mistress for a time even as he sent for Nell as an entertainer, as recorded by chronicler and politician Samuel Pepys in his diary in January 1668.7

In April 1668, while attending a play at the Duke’s Theatre called She Wou’d if She Cou’d, Nell sat adjacent to the box containing Charles and his brother James, Duke of York. King and actress chatted together, and afterward, accompanied by Buckingham’s cousin, went to dinner. It seems this dinner proved the tipping point for Nell and her relationship with the king.

Supposedly, Charles had no money with which to pay the tavern-keeper, and by some accounts:

…Nell herself who had to foot the bill, and that her exclamation against the company was prefaced by the King’s favourite expletive and said in perfect imitation of Charles’s deliberate, slightly Continental manner of speaking English: ‘‘Od’s fish! but this is the poorest company I ever was in!’ If true, she must have known that the money was well spent. Buoyed by the respect and sustained attention the King now paid her, Nell finally gave herself to the man who would be her lover and protector for the rest of her life.8

It’s important to note that Beauclerk, as a descendant of Charles and Nell, possibly preferred this account over other explanations. In any case, it’s likely we can date their relationship to early 1668. On May 8, 1670, Nell delivered a son named Charles Beauclerk, and King Charles acknowledged the child as his own. A second son named James followed on Christmas Day in 1671.

Nell & Louise de Kérouaille

The king’s affections, however, rarely remained singular. Around the same time of his son’s birth, Charles found another paramour in his sister’s retinue. Henrietta of England, Duchess d’Orleans, retained among her attendants a young French woman named Louise Renée de Penancoët de Kérouaille. Described as “famous for her beauty, though of a childish, simple, and somewhat baby face,” Louise hailed from a noble but impoverished Breton family.9

19th century French historian Henri Forneron offers a more sympathetic portrayal of Louise, observing that Charles “was tired of the furious temper of his dark Castlemaine, and of the vulgarity of Nell Gwynn. The conversation of the Breton blonde, who appeared sad and gentle, interested him. She also had the charming freshness of twenty, and the high delicate breeding which distinguished the court of Louis the XIV…”.10

In June 1670, she accompanied the Duchess to Dover, but Henrietta sadly died on June 30th. As a result, Charles made Louise a lady-in-waiting to his wife Catherine and soon took her to bed.

A rivalry grew between the earthly, sprightly, Protestant, and low-born Nell and the cool, composed, Catholic, and aristocratic Louise. Eleanor Herman, in Sex with Kings, cheekily remarked, “While most men dream of a woman who plays the lady in the parlor and the whore in bed, Charles effortlessly attained this fantasy by spending his days with cold, refined Louise and his evenings with lusty, bouncing Nell.”11

Nell reportedly poked fun at Louise - including wittily assigning her the nickname ‘Squintabella’ - and Cunningham recounts several instances of interactions between the two. The one quoted below is among the most well-known.

When Nelly was insulted in her coach at Oxford by the mob, who mistook her for the Duchess of Portsmouth, she looked out of the window and said, with her usual good humour, "Pray, good people, be civil; I am the Protestant ——— [whore]." This laconic speech drew upon her the favour of the populace, and she was suffered to proceed without further molestation.1213

Despite the rivalry inherent in competing for Charles’ attentions, Nell and Louise also occasionally found each other’s company tolerable, if not enjoyable. The disparity in their social status, however, often presented itself in different ways. For example, Charles raised Louise to the rank of Duchess of Portsmouth and made their son Duke of Richmond. Conversely, Nell did not receive a title nor a permanent residence until she pushed the king. Charles eventually gifted her the freehold of the crown-owned 79 Pall Mall, and their son Charles became the Earl of Burford, and, later, the Duke of St. Albans.

A Worthy Legacy

Although we may find amusement in Nell’s teasing of and banter with Louise, let’s not forget that not only did both women gain a measure of power in a time when women lacked significant advancement or economic opportunities, but Charles also seemed to care deeply for both of them. I know I did not touch on their relationship with Queen Catherine of Braganza, but it seems Louise, at least, respected the queen and enjoyed her company. In a world that revolved around the king, all of these women lived and served at his behest; and yet, in the case of Nell and Louise, their relationships offered them a form of security where they might otherwise have been left in dire straits.

Charles died on February 6, 1685, at the age of 44, leaving behind a dozen acknowledged illegitimate children from his many mistresses. Prior to his death, the king beseeched his brother to take care of Nell and Louise, as he still cared for both of the ladies.

Sadly, Nell passed away a couple of years later on November 14, 1687, after suffering a series of strokes. She left her estate to her surviving son Charles and was buried in the Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Louise de Kérouaille lived a long while longer, shedding her mortal coil on November 14, 1734, at the age of 85, leaving behind a son, Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond.

History remembers Nell Gwyn as something of a folk hero, a witty lass from the gutters who gallivanted amongst nobility whilst never forgetting her common origins. Louise de Kérouaille, on the other hand, receives a more negative reputation as a milk-white, mewling noblewoman who operates as a foil to Nell. Both women left worthy legacies as remarkable personages who attracted and kept the attention of a king as well as a made a life for themselves in Restoration England.

In the words of Peter Cunningham, in relation to Nell’s legacy:

Another [apology], if another is wanting, may be found in a far graver author, Sir Thomas More. "I doubt not,"—says that great and good man,—"that some shall think this woman (he is writing of Jane Shore) too slight a thing to be written of and set among the remembrances of great matters; but meseemeth" he adds, "the chance worthy to be remembered—for, where the King took displeasure she would mitigate and appease his mind; where men were out of favour she would bring them in his grace; for many that had highly offended she obtained pardon; of great forfeitures she gat men remission; and finally, in many weighty suits she stood more in great stead."—Wise and virtuous Thomas More,—pious and manly Thomas Tenison,—pretty and witty—and surely with much that was good in her—Eleanor Gwyn.14

Suggested Reading: The Story of Nell Gwyn by Peter Cunningham

Peter Cunningham’s The Story of Nell Gwyn traces Nell’s life, starting with her origins and ending with, well, her life’s end. The book was initially serialized in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1851 before its compilation into a complete volume. I found this biography remarkably well-sourced and an easy read. Cunningham positively views and admires Nell, offering a more sympathetic portrayal - an important bias to recognize - but the information contained within offers a solid introduction to her, even as written in the 19th century.

Other biographies about Nell Gwyn exist, but The Story of Nell Gwyn provides a good foundation for future research as Cunningham incorporates excellent primary and secondary sources. The WikiSource link shared below in the button includes plentiful research and annotative footnotes.

Related Artifact: Charles and James Beauclerk, Robert White

This 1679 line engraving by Robert White depicts Charles (1670-1726) and James (1671-1680) Beauclerk, the two sons of Nell Gwyn and Charles II. Charles acknowledged both of these children as his own and provided titles for his elder son as James died young. Charles received the titles of Baron of Heddington, Earl of Burford, and Duke of St. Albans. His descendants still hold the title of Duke of St. Albans to this day.

Artifact Description

Title: Line engraving of Charles and James Beauclerk

Creator: Robert White

Medium: Line engraving on paper

Date: 1679

Collection: National Galleries of Scotland

Sources & Further Reading

Beauclerk, Charles. Nell Gwyn: Mistress to a King. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2005.

Cunningham, Peter. The Story of Nell Gwyn. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1852.

Forneron, Henri. Louise de Keroualle, duchess of Portsmouth, 1649-1734:

society in the court of Charles II. London: S. Sonnenchein, Lowrey & Co., 1888.Herman, Eleanor. Sex with Kings. New York: Harper Collins, 2009.

Miyoshi, Riki. “A Tale of Two Theatres: Theatrical Rivalry between the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company, 1668-1672.” Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660-1700 40, no. 1 (2016): 25–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419381.

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4200/4200-h/4200-h.htm#link2H_4_0099. Accessed February 21, 2025.

If you enjoy this content, please consider buying me a coffee…or a pint…or a new book! Your support helps keep Musings of a Bookish Historian going and means the world to me. Thank you!

Featured image: Unknown woman, formerly known as Nell Gwyn, the studio of Sir Peter Lely, oil on canvas, c. 1675 (© National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3976)

Peter Cunningham, The Story of Nell Gwyn (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1852), 5.

Charles Beauclerk, Nell Gwyn: Mistress to a King (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2005), 9.

Ibid., 9-11.

Ibid., 33.

Ibid., 33.

The other was the Duke’s Company. The two companies maintained a fierce rivalry with each other, explored in further detail in Miyoshi, Riki. “A Tale of Two Theatres: Theatrical Rivalry between the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company, 1668-1672.” Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660-1700 40, no. 1 (2016): 25–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419381.

Samuel Pepys, “11 January 1668”, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4200/4200-h/4200-h.htm#link2H_4_0099 (accessed February 21, 2025).

Beauclerk, Nell Gwyn, 128-129.

Cunningham, The Story of Nell Gwyn, 113.

Henri Forneron, Louise de Keroualle, duchess of Portsmouth, 1649-1734:

society in the court of Charles II (London: S. Sonnenchein, Lowrey & Co., 1888), 56-57.

Eleanor Herman, Sex with Kings (New York: Harper Collins, 2009), 105.

Cunningham, The Story of Nell Gwyn, 121-122.

A satire published in 1682 recorded even further discourse between the two. See “A Dialogue between the Dutchess of Portsmouth and Madam Gwin at parting”, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, A35895.0001.001.

Cunningham, The Story of Nell Gwyn, 180-181.