A Gettysburg Maid: The Death of Jennie Wade

Jennie was the only civilian killed during the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg

The days of July 1st through July 3rd in 1863 saw one of the bloodiest conflicts of the American Civil War: the Battle of Gettysburg. In three days, the Unionists and the Confederates suffered approximately 50,000 casualties - consisting of those who were killed, wounded, missing, and captured. Most of these were soldiers. Among them, however, lay a twenty-year-old innocent civilian: Mary Virginia Wade.

Jennie Wade & The Battle of Gettysburg

Mary Virginia Wade - nowadays known as Jennie1 - was born on May 21, 1843 to James Wade and Mary Ann Filby. Following the breakdown of her father’s health and his commitment to an asylum, she and her mother worked as seamstresses on Breckenridge Street, in central Gettysburg. It’s possible the young woman was engaged to a granite cutter-turned-Union-corporal named Johnston Hastings Skelly.

On July 1, 1863, Jennie and her family made their way from their Breckenridge home down the road to her sister’s home on East Cemetery Hill. Jennie’s sister - Georgia Anne Wade McClellan - had just given birth, and her family arrived to help her as well as shelter from the encroaching skirmish.

Over the course of the next two days, Jennie and her mother served Union soldiers by offering them bread and water as the battle raged on. Union sharpshooters stationed themselves throughout the house, firing upon their Confederate counterparts in the nearby Rupp Tannery. Bullets and an occasional artillery shell continuously pelted the house.

On July 3rd, Jennie awoke early to fetch firewood and to knead dough for baking bread. The story goes that at approximately 7am, Confederate sharpshooters began firing in the direction of the McClellan house. Glass panes shattered, and bullets pierced wooden doors. Whilst in the kitchen preparing the bread dough:

[A] Confederate bullet, presumably from a sharpshooter’s rifle at the Rupp Tannery’s office, penetrated the outer door on the [house’s] north side, also the door which stood ajar between the parlor and the kitchen, striking the girl in the back just below the shoulder blade. The heart was hit, the bullet embedding itself in the corset at the front of her body. She fell dead without a groan.2

Over the years, Jennie’s tale - undisputedly tragic - has transformed from a historical footnote into something of a legend, replete with likely inaccuracies and embellishments.

How True is Jennie’s Story?

Jennie’s legend grew almost immediately in the aftermath of the Union victory in Gettysburg. Her innocence and support for the triumphant Unionists made her a prime candidate for adulation. Indeed, the last words Jennie supposedly spoke were, “If there is anyone in this house that is to be killed today, I hope it is me, as George [Georgia] has that little baby.”3 That’s certainly a turn of phrase that lends itself well to someone perhaps considered a martyr to the Union cause, even if accidental.

A 2019 article in Forensic Mag by Dr. John Anton offers a more forensic exploration of Jennie’s death and how the story compares to the author’s findings.

Put succinctly, the author posits that the given story of Jennie’s death may not match forensic evidence due to the following:

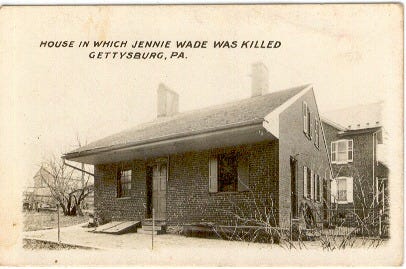

The preservational state of the McClellan house in which Jennie died does not match photographical evidence. The original exterior door through which the bullet contained a window, but the one presently at the McClellan residence (the one currently on display now) was added sometime after the house became the Jennie Wade House museum.

The shot missed the parlor door, meaning that the bullet did not pass through two doors as the story tells. Additionally, some accounts do not mention the parlor door at all. It’s possible, then, that the parlor door was open at the time of the shooting.

Anton indicates that the shot trajectory of the current exterior door and the parlor door is too steep to have struck Jennie.

Jennie was visible to her shooter. She could have been mistaken as a Union soldier due to the dark clothing she likely wore that morning. Additionally, Union troops may have been seen entering the McClellan house.4

Finally, on my recent trip to the battlefield, a tour guide suggested that a bullet made of soft lead likely would have flattened as it passed through two solid wooden doors. This correlates with Dr. Anton’s theory of the bullet passing through only one door.

We’ll likely never know the entirety of Jennie’s story. However, her courage and service to the Union cause should not be forgotten.

The house in which she was killed is now a museum known as the Jennie Wade House museum. Outside of the Jennie Wade House stands a memorial to this remarkable woman.

She now rests in Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery. An American flag flies perpetually over her grave, one of the only two women who have that honor (the other being Betsy Ross). A fitting tribute to one whose spirit still inspires us generations later.

Sources & Further Reading

“Mary Virginia ‘Jennie’ Wade.” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/mary-virginia-jennie-wade.

Anton, John A. “History’s Revolving Door: A Forensic Interpretation of the Slaying of Mary Virginia Wade.” Forensic Mag. March 6, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190306002711/https://www.forensicmag.com/news/2019/03/historys-revolving-door-forensic-interpretation-slaying-mary-virginia-wade-gettysburg.

Johnson, J.W. The true story of “Jennie” Wade, a Gettysburg maid. Rochester, NY: J.W. Johnston, 1917.

According to John White Johnston, author of The true story of “Jennie” Wade, a Gettysburg maid, Virginia went by “Gin” or “Ginnie”, but a newspaper inaccurately gave her the nickname “Jennie”, a name that has persisted to this day.

John White Johnson, The true story of “Jennie” Wade, a Gettysburg maid (Rochester, NY: J.W. Johnston, 1917), 23.

Ibid., 21.

John A. Anton, “History’s Revolving Door: A Forensic Interpretation of the Slaying of Mary Virginia Wade,” Forensic Mag, March 6, 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20190306002711/https://www.forensicmag.com/news/2019/03/historys-revolving-door-forensic-interpretation-slaying-mary-virginia-wade-gettysburg. Please note that this is an archived copy of the article and does not contain the referenced images.