Issue No. 22: Of Lackland & Landing Lackies

King John Lackland, almost-king Louis, and arguably Mel Brooks' best movie.

Welcome back, dear readers! In this week’s issue, you’ll learn about a thirteenth-century invasion that almost changed the course of English history. Additionally, I share the book that I’m currently reading as well as one of the few extant copies of the Magna Carta, the document which transformed the relationship between king and country and influenced developing governments centuries later.

But first, here’s one of my favorite clips about the historical character you’ll meet this week:

In this clip from one of my all-time favorite movies Robin Hood: Men in Tights, King Richard the Lionheart (Patrick Stewart) returns from the Crusades to find his brother John (Richard Lewis) attempting to usurp his authority and claim the throne. Before the guards take him away, King Richard proclaims that all toilets in the realm will therefore be known as “johns”, an allusion to the colloquial term.

In actuality, the term most likely dates from the sixteenth century. But it’s a mark of Mel Brook’s humor and brilliance that such a joke was included in this iconic movie.

Now, let’s learn a little more about King John and his illustrious…I mean, notorious…regime.

King John of England & the King That Almost Was

English history is full of both well-respected kings and ones who became dastardly villains. King John (r. 1177-1216), perhaps not as comically terrible as depicted in Men in Tights, falls to the latter end of the spectrum, boasting a reputation as one of England’s worst kings.

That reputation has lasted throughout the centuries, except for a brief resurgence of support and sympathy courtesy of Thomas Cromwell during the English Reformation.1 Such was John’s kingly performance that his barons threatened a revolt, forcing the Angevin monarch to agree to their terms and affix his seal to a document called Magna Carta in 1215. This document expressed in writing for the first time the belief that a king and his government could not set themselves above the law. The conflict between king and country erupted into an internal war in 1215, catalyzed by a foreign adversary and claimant to the English throne.

John’s Early Years & a Matter of Inheritance

John was born on Christmas Eve in 1166 at Beaumont Palace in present-day Oxford, England. The prince boasted an illustrious lineage - his father, King Henry II, descended from William the Conqueror while his mother, Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, was renowned for her beauty, wit, artistic and cultural patronage, and her participation in the Second Crusade. At the time of his birth, John seemed the least likely candidate for the English throne as three elder brothers - Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey - preceded him in the line of succession.

Interestingly, the concept of patrilineal primogeniture hadn't yet solidified as the primary method of inheritance in England in the twelfth century. That is, fathers typically distributed titles and lands across their sons rather than the eldest son inheriting everything. As a result of this form of inheritance, John was not expected to receive substantial holdings from his father at the time of his birth as a fourth son. Indeed, Henry affectionately christened John with the epithet “sans Terre”, or, in English, “Lackland”.

And yet, Henry sought to bestow John, allegedly his favorite son, with his favor in other ways. The king arranged an advantageous marriage for his son, granted him castles and future possessions in France, and named him Lord of Ireland. When John's first betrothed passed away, however, he lost his initial inheritance.

John's situation changed drastically as he matured. His brother Henry the Young King (so-called because he co-ruled alongside Henry II) died in 1183 of dysentery, brother Geoffrey died in 1186 from injuries sustained during a tournament, and his father Henry II died in 1189. The succession of events catapulted Richard to the throne, and he was crowned at Westminster Abbey in September 1189. John suddenly moved into a much more prominent role as one of the heirs apparent to the Angevin throne.

The Reign of Richard I & a Succession Crisis

During Richard's reign, John's future seemed secure. Richard named John as Count of Mortain, bestowing upon the prince English lands. John also married Isabella of Gloucester, a wealthy heiress, in August 1189, becoming the Earl of Gloucester jure uxoris (by right of his wife). It was clear by the early 1190s that John had his eye on his brother’s throne.

Between 1191 and 1194, while Richard fought in the Crusades, John attempted to usurp the king’s position through bribery and strategic positioning in key locations. Lackland pushed especially hard after Duke Leopold of Austria captured Richard on October 9, 1192, even pursuing an alliance with the French king Philip Augustus. Richard’s officers, ruling the kingdom in his stead, refused his overtures.2

On April 6, 1199, Richard I died, sparking a succession crisis as he left behind no legitimate children. Two contenders for the Angevin throne emerged: John, the youngest brother, and Arthur, Geoffrey's son and John's nephew.

Having failed to usurp Richard's position in the early 1190s, John seized the opportunity for the throne and ascended on May 27, 1199. He imprisoned Arthur, and the young heir presumably died, supposedly murdered by John in a drunken rage, around 1203. To protect his throne, the king also jailed his niece, Eleanor of Brittany, another with a valid dynastic claim.3

His rule, however, would be far from secure.

The Coming of Prince Louis and the Conflict of 1216-1217

I could wax at length about John’s successes and failures as king, but that’s not the point of this post.4 John’s reign and failures - actual and perceived - sowed discontent among some of his barons, even post-Magna Carta. These included, among others:

Persecution of barons and their families

Loss of French territorial possessions especially Normandy and Anjou

The transformation of England into a papal vassal

Forcing his barons into debt

Cruelty to prisoners

General tense relations with his barons

The bitter relationship between John and his magnates erupted into a civil conflict between 1215 and 1217. Known as the First Barons’ War, the conflict saw the English monarchy balancing precariously on the edge of a knife. Rebellious barons invited Prince Louis (later Louis VIII), the son of the aforementioned Philip Augustus, to invade England and overthrow John.

How did Louis claim the throne? Jure uxoris, by right of his wife. Louis’s wife, Blanche of Castile, was the granddaughter of Henry II and John’s niece. The prince’s father and the Church did not approve of the venture. Indeed, Pope Innocent III excommunicated Louis, meaning that he could not attend mass, receive the rites of the Church, or, on the event of his death, be interred in holy ground.

Over the next year, Louis gained ground in England. The rebel barons proclaimed him king in London but failed to crown him. At its apex, Louis’ campaign granted him control over half of England.

After John’s death on October 18, 1216, the fight continued under his son Henry III and Henry’s regent William Marshal. Louis failed to gain much headway in England as rebels slowly but surely defected back to the royalists after a series of military and naval victories.5

After the Second Battle of Lincoln on May 20, 1217, the invading foreign forces fell apart. Louis’s wife Blanche sent reinforcements from France. However, English forces met the French navy in battle outside of the city of Sandwich on August 24, 1217. That spelled the end of Louis’s English ambitions. The Treaty of Lambeth, signed on September 11, 1217, saw Louis renounce his claims to the throne and the withdrawal of his troops in exchange for 10,000 marks.

The First Barons’ War is a much overlooked conflict in English history but one that had the makings of a pivotal event on par with the Battle of Hastings, the Battle of Agincourt, and many more that changed the course of English history.

Book of the Week: 1217 by Catherine Hanley

The content above serves as context for my next book review! Author and medievalist Catherine Hanley has written an extensive history on the First Barons’ War in her book 1217. She seeks to cover a relatively unknown civil war in history, one that could have seen a very different English history had Louis won the war and assumed the throne.

1217 covers the precursor, the duration, and the aftermath of the First Barons’ War. From the first siege of Dover to the Second Battle of Lincoln, Hanley promises to deliver an excellent and worthwhile introduction to this topic, one that’s been shamefully missing from early medieval historiography.

As someone who’s fairly well-versed in English history, I will admit I had not heard of this conflict. But, Hanley’s approachable prose without sacrificing historical details, depth, and accuracy make this a topic easily digestible for any fan of English history. I look forward to providing a review on Monday!

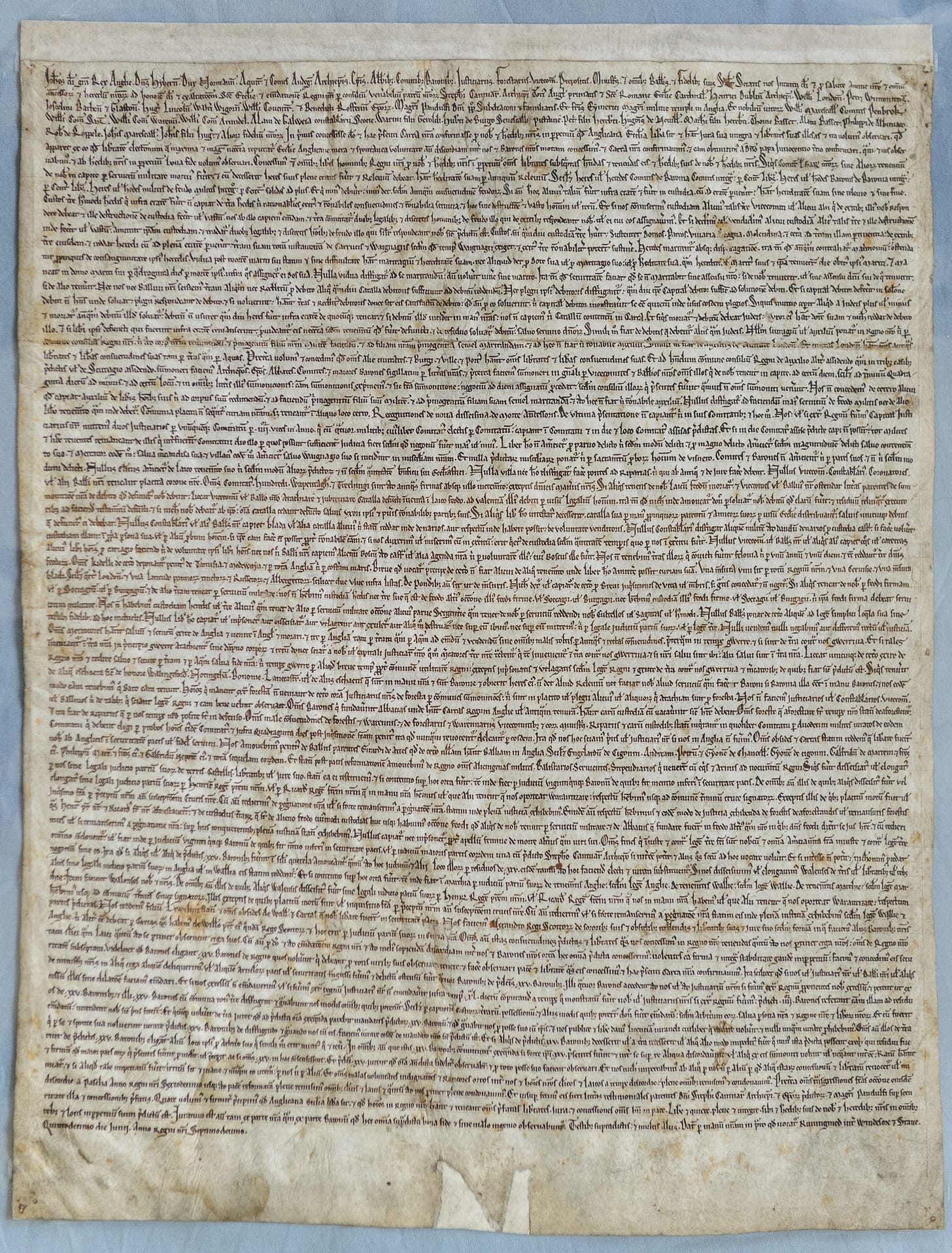

Artifact of the Week: Extant Copy of Magna Carta

Few extant copies of Magna Carta exist, but this one survives on loan at the American National Archives. Produced in 1297, this copy was created several decades after the original, but it nonetheless holds incredible historical value.

According to the National Archives:

This copy of the Magna Carta was in the possession of the Brudenell family, the earls of Cardigan by the 17th century. It was acquired by the Perot Foundation in 1984 and purchased by David M. Rubenstein in 2007. David Rubenstein has placed Magna Carta on loan to the National Archives as a gift to the American people.

Magna Carta, the National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6116690.

It’s quite fascinating that this remarkable document, one that inspired the articles of America’s founding, is available for anyone to see.

Artifact Description

Title: Magna Carta

Place of Production: England

Material: Parchment

Date: 1297

Collection: The National Archives, courtesy of David Rubenstein

Thank you for joining me this week! Have a great weekend!

Cheers,

Featured image: An engraving of King John signing the Magna Carta on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede, England (Photos.com/Getty Images)

For a more full discussion, see Carole Levine, “A Good Prince: King John and Tudor Propaganda”, The Sixteenth Century Journal 11, no. 4 (1980), 23-32.

For more information on this, see Stephen Church, King John and the Road to Magna Carta (New York: Basic Books, 2015), Chapter 4. According to Church, John’s actions “revealed him to be a risk taker of extraordinary proportions, prepared to chance everything, including the very future of his dynasty….”

This is arguably one of the most despicable things John ever did: imprisoning an innocent woman. Eleanor spent the rest of her life in monastic captivity.

Was John a bad king? I feel it’s a nuanced conversation, but signs point to how John really wasn’t all that atypical for a medieval king. A more thorough examination of his reputation among historians (as of the 1960s) can be found in C. Warren Hollister, “King John and the Historians,” Journal of British Studies 1, no. 1 (1961), 1-19.

These include the second siege of Dover, the Second Battle of Lincoln, and the Battle of Sandwich. The prince’s forces also saw harassment from the forces of William of Cassingham, a country squire and possible inspiration for Robin Hood.