Issue No. 24: Of Chains & Continentals

The fertile Hudson River Valley and the chain that bridged it during the American Revolution.

Welcome back, my friends! This week’s been buzzing for me as I’ve been working on a website revamp, endeavors in coaster-making, and attempts to maybe (eventually) launch more products in my online store. Never a dull moment, right?

This week’s issue focuses on a lesser-known aspect of the American Revolution: the Great West Point Chain that bridged the Hudson River in an effort to prevent British efforts to separate the colonies and interrupt their supply chains.1 The chain’s creation also forms the focal point of this week’s book: The General’s Watch by Kiersten Marcil. Finally, some chain links from this engineering marvel survive to the present-day and offer a tangible connection to a pivotal point in America’s history.

The History of the Great Hudson River Chain

Introduction

During the American Revolution, the Hudson River and the Hudson Valley played an immensely important role, both in terms of navigation and military maneuvers. According to West Point, “the Hudson River was not only the primary trade route connecting Canada and the Great Lakes to New York City, but also decisive terrain in military operations throughout the colonial era.”2

In a letter dated November 22, 1776, Henry Wisner and Gilbert Livingston - both members of the Secret Committee to the New York Committee of Safety3 - wrote to the Committee that they had sounded [ascertained the depth] of the Hudson River in an effort to recommend appropriate locations for the placement of obstacles to hinder British movements.4 It was hoped that these obstacles would hinder British troop movements through upstate New York.

Such barriers took a few different forms:

Cheval de frise - a barrier constructed of logs in an elongated X-form, or a similar structure constructed with wooden or metal spikes sticking out of the barrier; originally used as an anti-cavalry obstacle

Chevaux-de-frise before Confederate main works, St. Petersburg, VA, 1860s | ©Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, cwpb.02598 Boom - an obstacle that floats on the water’s surface; different forms; one type looked like a ladder with logs suspended between two chains

Chain - a metal chain that’s either sunk into water or floated on the water’s surface, supported by rafts

Could such obstacles bridge the Hudson? And, if so, who would be the one to manage such a daunting feat? After all, as Hugh T. Harrington wrote in The Journal of the American Revolution in 2014:

The Hudson however is a far mightier river than the Delaware and proved much more formidable than the amateurs who attempted to control it. At the upper end of Manhattan Island, between Fort Washington on the Manhattan side and Fort Lee on the New Jersey side of the river (roughly where the George Washington Bridge now stands), the depth of the shipping channel is between 18 and 50 feet. The channel itself is over 2400 feet wide which makes almost any sort of obstruction at this point impractical.5

It would take a talented individual to oversee the construction, and fortunately, General George Washington knew of one such individual: artillery officer Captain Thomas Machin.

Machin and the Construction of the Hudson River Chain

(It’s not my intention to delve into the very specifics of the chain’s construction. Others more well-versed in the research such as Harrington and Merle Sheffield have extensively covered the subject.6)

In response to the Secret Committee’s November 1776 recommendations, George Washington placed Machin in charge of fortifying the Hudson Highlands. Initially, a chain and boom had been constructed at Fort Montgomery, stretching across the river to the western bank. However, a faulty link caused the barrier to fail, and Machin oversaw the chain’s repair. The British breached the obstacles in October 1777 and took the military fortifications. In the aftermath, Machin decided to build a different chain at West Point a short distance away.

Given that the Fort Montgomery chain failed due in part to its cobbled construction of mismatched links, Machin decided to take a more uniform approach:

Machin chose the Sterling Iron Works of Chester, New York to forge the chain. Machin had worked with them in the past and was confident they could make his massive chain and the supporting hardware. The chain had to be strong, twice as strong as the Fort Montgomery Chain, yet it had to be light enough that it could be taken up each Fall and installed again in the Spring.7

Though measurements of individual links varied, that one company forged the chain meant that (hopefully) all of the components were formed of a similar composition. Construction occurred over a period of about six weeks. Each chain link measured about two-feet long, weighed between 140 and 180 pounds, and were placed on floating log rafts. In sum, the put-together chain measured about 600 yards in length and weighed about 65 tons.

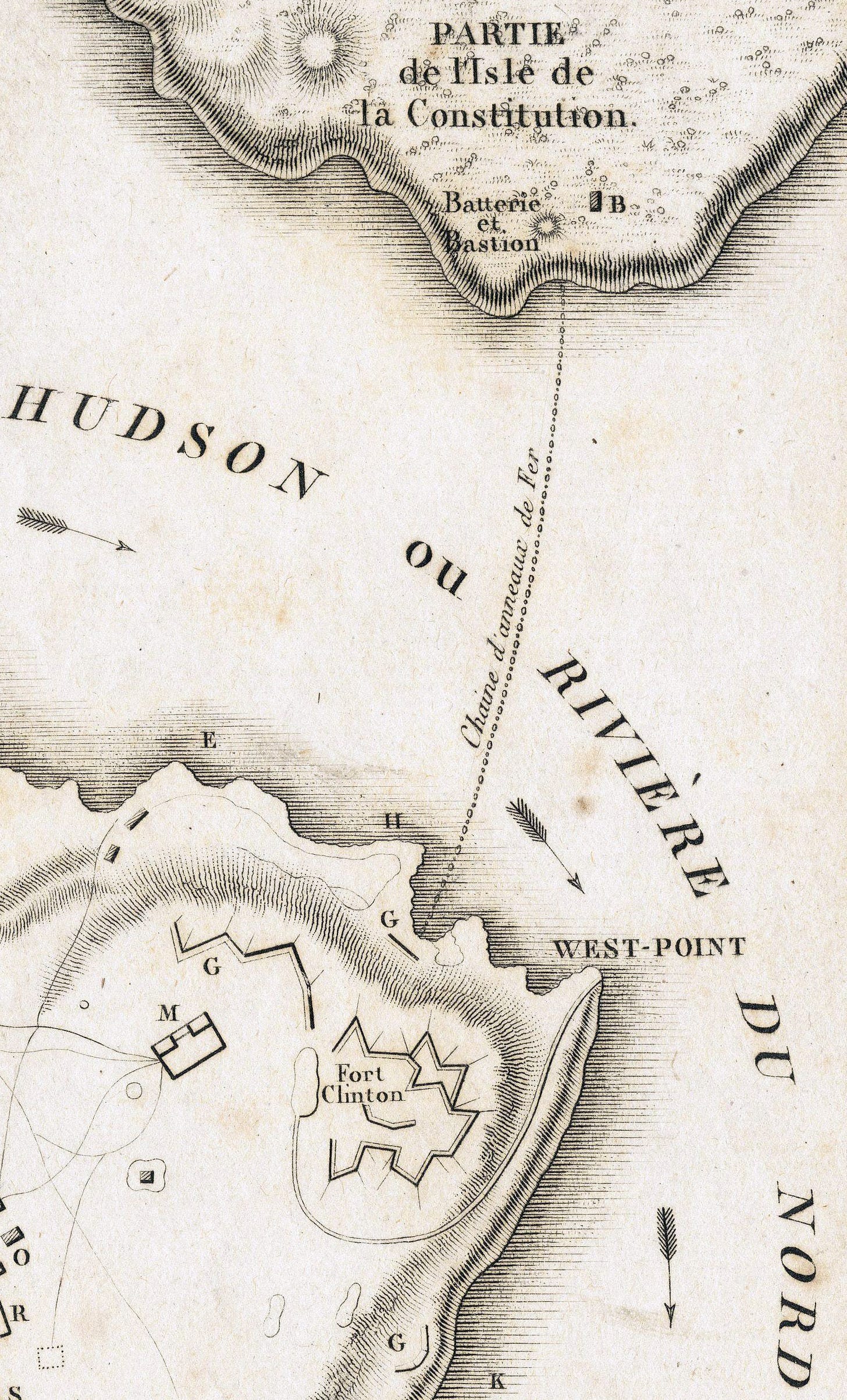

Machin and other leaders decided to emplace the chain on an S-shaped bend in the Hudson River. The tight and narrow curve made river navigation difficult and proved ideal for staving off any British incursions. When completed, the chain stretched from West Point across the river to Constitution Island with defensive batteries protecting the chain and the riverbanks.

The Great Hudson River Chain lasted until the end of the war without any attempts by the British to test it. Afterwards, it lay on the river shore, rusting, for the next two decades until the decision came to melt it down in 1829. Some chains remained preserved and currently exist in a number of places including at the West Point Military Academy and the New York State Capitol.

Although the Great Hudson River Chain never actually saw service, it nonetheless remained an important - though not as well-known - part of the American Revolution.

Book of the Week: The General’s Watch by Kiersten Marcil

In Kiersten Marcil’s debut novel Witness to the Revolution, a young woman mysteriously appears in revolution-era America, as if out of nowhere. Savannah Moore quickly adapts to the times and befriends a handsome but almost-otherworldly man named Captain Jonathan Wythe, a man whose existence belies his Continental appearance and allegiance.

In case you missed my initial review of Witness to the Revolution, here it is again!

In The General’s Watch, Kiersten Marcil’s thrilling sequel to Witness to The Revolution, Savvy slowly pieces together the circumstances in which she finds herself, the darkness holding her hostage, and her connection to the dashing captain. The Great Hudson River Chain, described above, plays a key role in this story. If you choose to read it, the information provided should give you a good reference point!

Look for my review on this book on Monday!

Artifact of the Week: Great Hudson River Chain Links

The links shown below formed part of the Great Hudson River Chain that spanned the river from West Point to Constitution Island from 1778 until 1783. The chain protected that stretch of the Hudson River in order to prevent British troops from breaking Continental supply chains and dividing the colonies.

After the American Revolution concluded, the chain was mostly melted down for scrap metal, but some links were preserved. Some reside at West Point, the New York State Capitol, and in other locations.

Artifact Description

Title: Great Hudson River Chain links

Date: c. 1778

Material: Iron

Location: New York State Capitol

Thank you for joining me this week! Enjoy your weekend and stay cool!

Cheers,

Featured image: Photograph of the Hudson River chain links, C. Manley DeBevoise (New York Public Library, b19745455)

Hugh T. Harrington, “The Great West Point Chain,” The Journal of the American Revolution, September 25, 2014, https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/09/the-great-west-point-chain/.

“The Hudson Valley During the American Revolution,” West Point Military Academy, https://www.westpoint.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/digital-history-center/projects/the-hudson-valley-the-american.

Committees of safety (along with committees of correspondence and committees of inspection) were local groups of Patriots during the American Revolution that effectively governed their regions or colonies, especially against loyalists to the British cause. Their duties included passing, enacting, and enforcing laws; training and raising militias; suppressing loyalists; regulating the economy; and more.

“Letter from Henry Wisner and Gilbert Livingston to New-York Committee of Safety: Soundings of Hudson River, in the Highlands,” November 22, 1776, S5-V3-P01-sp20-D0476, Northern Illinois University Digital Library, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A103565.

Harrington, “The Great West Point Chain.”'; Lincoln Diamant, Chaining the Hudson, the Fight for the River in the American Revolution (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1994), 41.

See Harrington, “The Great West Point Chain,” and Merle Sheffield, “The Chain and the Boom,” Hudson River Valley Institute.

Harrington, “The Great West Point Chain.”