Issue No. 33: Of Klondike Gold & Chronicling Glory

The Klondike Gold Rush, Eric A. Hegg, and documenting the last great North American migration of the 19th century.

“Up the golden stairs they went, the men from the farms and the offices, climbing into the heavens, struggling to maintain the balance of the weight upon their shoulders, occasionally sinking to their hands and knees but always rising up again, sometimes breaking down in near-collapse, sometimes weeping in rage and frustration, yet always striving higher and higher, their faces black with strain, their breath hissing between their gritted teeth, unable to curse for want of wind yet unwilling to pause for respite, clambering upward from step to step, hour after hour, as if the mountain peaks themselves were made of solid gold.” ~ Pierre Berton

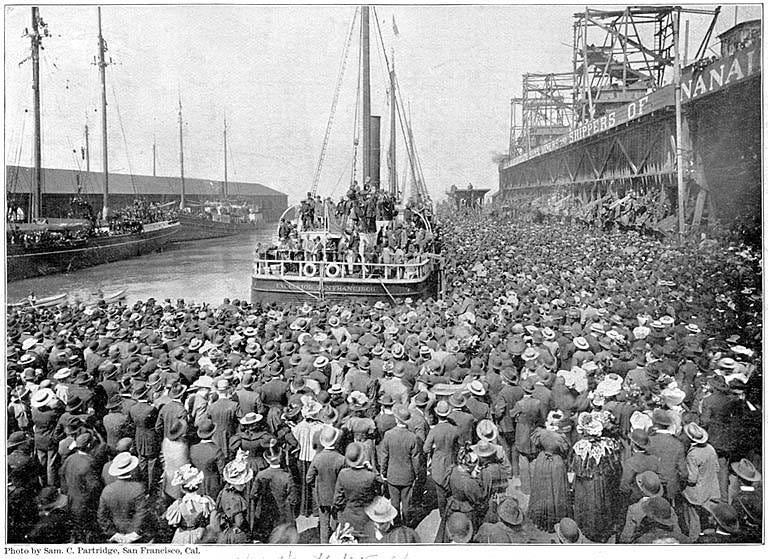

Writing in 1900, Edwin Tappan Adney, a special correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, described quite a remarkable spectacle that excited the city of San Francisco, California, in June 1897:

“On the 16th of June, 1897, the steamer Excelsior…steamed into the harbor of San Francisco and came to her dock on Market Street. She had on board a number of prospectors who had wintered on the Yukon River. As they walked down the gang-plank, they staggered under a weight of valises, boxes, and bundles. That night the news went East over the wires, and the following morning the local papers printed the news of the arrival of the Excelsior with a party of returned miners and $750,000 in gold-dust, and the sensational story that the richest strike in all American mining history had been made the fall of the year before on Bonanza Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River, a small stream entering the Yukon not far above the boundary-line between American and Canadian territory…”1

A similar occurrence happened in Seattle, Washington:

“On the 17th, the Portland…arrived at Seattle with some sixty more miners and some $800,000 in gold-dust, confirming the report that the new find surpassed anything ever before found in the world.”2

News of the glittering finds near the American-Canadian border spread across the United States and the world like wildfire, prompting a mass surge of people to the region in search of gold. We know this event as the Klondike Gold Rush (also known as the Yukon Gold Rush).

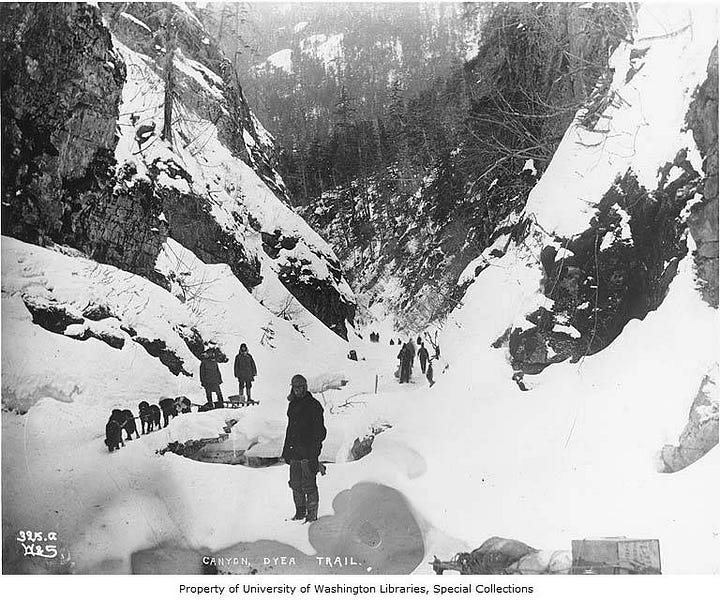

Many journalists and photographers chronicled the sudden spectacle, including a Swedish-American photographer named Eric A. Hegg. His photos of this remarkable event - from the unforgiving trails and throngs of would-be prospectors to life in the mining camps - grant us unparalleled visual insight into one of the last great migrations of the nineteenth century.

Eric A. Hegg & Chronicling the Klondike Gold Rush

Brief Overview of the Klondike Gold Rush

Getting to the Klondike

I could wax at length about the Klondike Gold Rush for pages, though I suspect you’d be ready to hit that “unsubscribe” button pretty quickly. So, I’ll try to keep this as brief as I can.

The search for gold in the Yukon began in the 1870s, but an August 1896 discovery catalyzed the rush. American prospector George Carmack, his Tagish First Nations wife Shaaw Tláa (also known as Kate Carmack), her brother Keish (Skookum Jim Mason), and Keish’s nephew K̲áa Goox̱ (Dawson Charlie) found gold along the banks of Rabbit Creek - one of the river’s tributaries. They staked out and registered four claims and continued prospecting, finding significant gold deposits. As a result, they became wealthy, and Rabbit Creek gained a new name: Bonanza Creek.

The find sparked the Klondike Gold Rush, a journey encompassing hundreds of miles via overland, all-water, and hybrid routes. The White Pass Trail and the Chilkoot Trails comprised the most common routes, but plenty of others promised travelers passage to the fabled north. The White Pass Trail - a longer but slightly easier route - began in the frontier town of Skagway, Alaska, and the Chilkoot - a shorter but steeper and difficult trail - originated in Dyea, three miles from Skagway. Congestion, muddy trail conditions, obstacles, disease, inclement weather, and more plagued gold-seekers on each route.

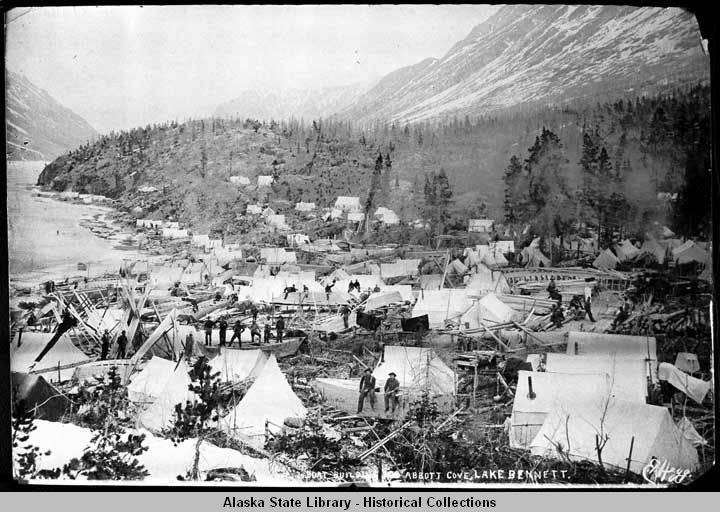

Once a gold-seeker braved the early trails, ascended the summits, and crossed the American-Canadian border, they reached Lake Bennett and the headwaters of the Yukon River. From there, travelers took to the river, navigating through treacherous rapids and watercourses. The final stop lay in Dawson City, a mining camp-turned-boom town.

Approximately 100,000 stampeders started out for the Klondike. Of these, between 30,000 and 40,000 made it to Dawson City. Only a few hundred struck it rich.

Life in a Gold Rush Town

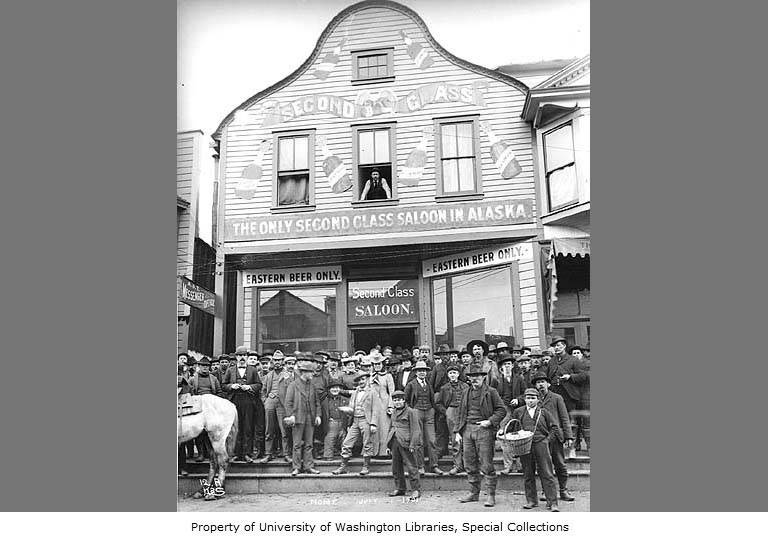

One might think life in a booming mining town resembled that of a frontier town in the American West. In many cases, this was true. Residents threw up ramshackle buildings as prospectors streamed into town. Scarcity of land, goods, and necessities increased prices. Grime-encrusted miners, wealthy businessmen, dance hall girls, goods-hawking merchants, Dawson proprietors, and more crowded into saloons.

Saloons especially formed the “centre of social life” in the Yukon. “At Dawson, shut out from the world, under conditions that tried the very souls of men, it was less wonder that men were drawn together into the only public places where a friendly fire burned by day and night, and where, in the dim light of a kerosene lamp, they might see one another’s faces.”3

Where the gold rush experience differed - whether in the Klondike or California or any other mining town - was typically in the locale’s longevity. In Dawson City, for example, the population peaked between 16,000 and 17,000 at the height of the gold rush in 1898. By 1902, however, the population fell to about 8000. In many cases, entire mining communities transformed into ghost towns once prospectors exhausted ore deposits.

And yet, people found ways to “civilize” the Great North and earn a living, especially women. Opportunities for women included owning and operating various businesses such as laundrettes, restaurants, and boarding houses; living in the raucous camps as a demimonde; selling their domestic services; and even prospecting in small capacities. Some - such as Belinda Mulrooney - even opened up hotels with decadent settings and decent food to offer guests a more refined experience. Dawson even had an opera hall that gave vaudeville performances. Little reason, then, that Dawson came to be known as “the Paris of the North”.

Photographing the Klondike Gold Rush

The Klondike Gold Rush inspired journalists, photographers, poets, artists, and many more to document its history through poems, books, journals, diaries, and photos. One of my favorite chroniclers was Eric A. Hegg (1867-1947), a Swedish-American photographer who initially set up a studio in Dyea and later Skagway in 1897. He and fellow photographer Per Larrs documented stampeders who trudged along the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails, selling their images along the way. According to the University of Washington, “Along the trails they recorded the sail driven sleds, temporary tent towns, piles of snow covered food caches and the many hardships endured by the Klondikers as they neared their goal.”4

In June 1898, Hegg ventured north to Dawson City, where he and Larrs opened a studio on the riverfront between First and Second Streets. The pair continued to capture the daily life and hardships of miners. He maintained his studios in both Skagway and Dawson City for a while before selling his stake in the Dawson one in July 1899. Upon leaving the Yukon, Hegg followed and documented the Nome gold rush, spending a couple of years on the Seward Peninsula in Alaska.

In the early-1900s, Hegg continued to work in Alaska, specifically Juneau and Cordova as a company photographer for the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad. We don’t know precisely when he left Alaska, but upon his departure, he worked for a San Francisco newspaper in Hawai’i for a time before passing away in December 1947.

Hegg’s photographs immerse us in a time and place far different than our own. The Klondike conjures up a myriad of images: vessels of all shapes and sizes crowding Seattle's shores while grizzled prospectors hoist golden nuggets into the air to the sounds of cheering celebrants; the intangible promise of leaving behind one's life for the chance to embark on the adventure of a lifetime to the desolate reaches of the Yukon Territory; gold rush boomtowns brimming with glittering characters, scantily-clad women of the frontier demimonde, silver-tongued confidence men and their sly lackeys, and dirt-clad, inexperienced cheechakos whiling away the hours in drink and ribald conversation; and the firm belief in a frigid Manifest Destiny where the faithful will find their own slice of a gilded heaven.

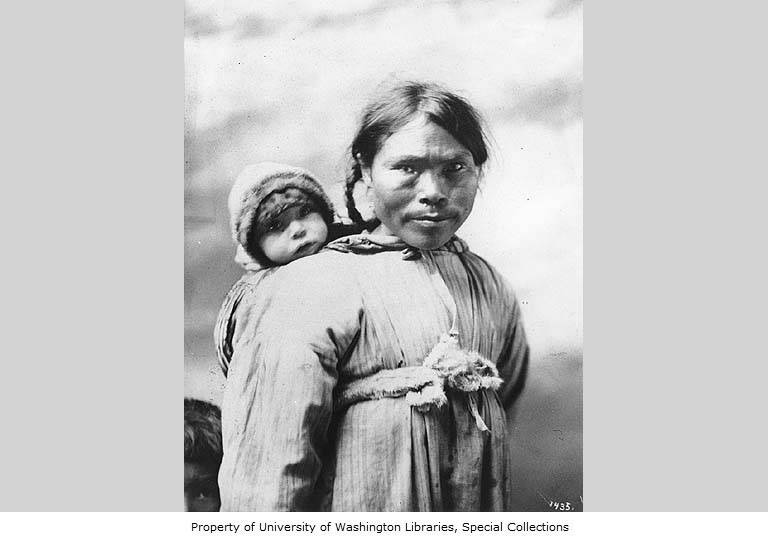

In short, Hegg portrays the realism of the trials and tribulations stampeders faced during the Klondike Gold Rush. He also humanizes these gilded tales, making for a much more fascinating and poignant story. It’s easy to get caught up in the glitz and glamour of the gold rush with a strong desire to romanticize the past. However, we should also recognize the environmental effects and cultural impacts to the First Nation Tribes, something rarely discussed in the general historiography. It’s my hope to shed light on this in the future, but for now, enjoy some photos from Eric A. Hegg!

Suggested Reading: The Call of the Wild by Jack London

Did you know that famed American author Jack London spent time in Dawson City during the gold rush? He traveled to the area in 1897, but like many others, he did not strike it rich. Nonetheless, the journey and experiences he had inspired him to write a few books set in the North. Among the most prominent of these is The Call of the Wild.

The Call of the Wild is a novel about a wolf-dog hybrid named Buck who undergoes a hero’s journey of his own in which his primal and domestic instincts war at one another against the beauty and cruelty of a man’s world. It’s not a long read, but the novel offers an apt characterization of the Yukon and the balance of civilization and frontier embodied in the gold rush.

Related Artifact: Souvenir of Alaska and Yukon Territory, Eric A. Hegg

In 1900, Eric A. Hegg released a booklet comprised of a number of his photographs from his time spent in Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Some subjects include indigenous people, vessels, buildings, trails, landscapes, and transportation. It’s an excellent showcase of his talent, and the book is freely available online via HathiTrust.

Artifact Description

Title: Souvenir of Alaska and Yukon Territory booklet

Creator: Eric A. Hegg

Medium: Paper

Date: 1900

Sources & Further Reading

Adney, E. Tappan. The Klondike Stampede. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1900.

Berton, Pierre. Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899. Toronto: Penguin Books Canada, 1972.

Gates, Michael. "Klondike Gold Rush." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. 2009. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/klondike-gold-rush. Accessed March 14, 2025.

If you enjoy this content, please consider buying me a coffee…or a pint…or a new book! Your support helps keep Musings of a Bookish Historian going and means the world to me. Thank you!

Featured image: Klondikers at The Scales and ascending to the summit of Chilkoot Pass, Alaska, Eric A. Hegg, photograph, c. 1898 (© University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, HEG384)

E. Tappan Adney, The Klondike Stampede (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1900), 1-2.

Ibid., 2.

Ibid., 336-337.

“Hegg (Eric A.) Photographs of Alaska and the Klondike, 1897-1901,” University of Washington Libraries, https://content.lib.washington.edu/heggweb/index.html, accessed March 17, 2025.

Great article, Amy. It makes me want to learn more about the Klondike Gold Rush and reminds me to reread Call of the Wild. Hegg's photos are fantastic.